One of the most common questions about GEPA: how does it actually use data?

The short answer: GEPA splits your data into two sets. Understanding why is key to understanding the whole system.

The Key Insight: Two Different Purposes

Think of preparing for a big exam. You wouldn't take the final exam as practice — you'd use practice problems to learn, then face the real exam to prove what you know.

GEPA works the same way:

| TRAINSET | VALSET | |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Learning | Scoring |

| Question it answers | "What went wrong? How can we improve?" | "How good is this prompt really?" |

| How much is used | Small minibatch (3-5 examples) | Full set |

| Output | New candidate prompt | Scores for Pareto frontier |

In simple terms:

- Trainset = Practice problems you study with, make mistakes on, learn from

- Valset = The actual exam that determines your grade

Step-by-Step Walkthrough

Let me trace through a complete iteration with concrete examples.

Setup: Our Example Data

# Training set: 9 math problems (we learn from these)

trainset = [

{"id": "T1", "question": "What is 2+2?", "answer": "4"},

{"id": "T2", "question": "What is 5×3?", "answer": "15"},

{"id": "T3", "question": "If x+3=7, what is x?", "answer": "4"},

{"id": "T4", "question": "What is 10÷2?", "answer": "5"},

{"id": "T5", "question": "John has 3 apples, buys 4 more. How many?", "answer": "7"},

{"id": "T6", "question": "What is 8-3?", "answer": "5"},

{"id": "T7", "question": "Solve: 2x=10", "answer": "x=5"},

{"id": "T8", "question": "What is 7+8?", "answer": "15"},

{"id": "T9", "question": "A rectangle has length 5, width 3. Area?", "answer": "15"},

]

# Validation set: 4 different problems (we measure performance on these)

valset = [

{"id": "V1", "question": "What is 9+6?", "answer": "15"},

{"id": "V2", "question": "Solve: 3x=12", "answer": "x=4"},

{"id": "V3", "question": "Sara has 8 cookies, eats 3. How many left?", "answer": "5"},

{"id": "V4", "question": "What is 6×7?", "answer": "42"},

]

# Starting prompt

seed_candidate = {

"instruction": "Answer the math question."

}

Iteration 0: Initialize and Score Seed

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ ITERATION 0: INITIALIZATION │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ Step 0.1: Create initial state │

│ ───────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ candidates = [ │

│ { │

│ "instruction": "Answer the math question." │

│ } │

│ ] │

│ │

│ pareto_scores = { │

│ 0: {} ← Candidate 0 has no scores yet │

│ } │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Step 0.2: Evaluate seed candidate on VALSET │

│ ─────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ VALSET EVALUATION (not trainset!) │

│ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ V1: "What is 9+6?" │ │

│ │ Prompt: "Answer the math question." │ │

│ │ Model output: "15" │ │

│ │ Correct answer: "15" │ │

│ │ Score: 1.0 ✓ │ │

│ ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ V2: "Solve: 3x=12" │ │

│ │ Prompt: "Answer the math question." │ │

│ │ Model output: "36" (wrong! didn't solve for x) │ │

│ │ Correct answer: "x=4" │ │

│ │ Score: 0.0 ✗ │ │

│ ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ V3: "Sara has 8 cookies, eats 3. How many left?" │ │

│ │ Prompt: "Answer the math question." │ │

│ │ Model output: "11" (wrong! added instead of subtract)│ │

│ │ Correct answer: "5" │ │

│ │ Score: 0.0 ✗ │ │

│ ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ V4: "What is 6×7?" │ │

│ │ Prompt: "Answer the math question." │ │

│ │ Model output: "42" │ │

│ │ Correct answer: "42" │ │

│ │ Score: 1.0 ✓ │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ Updated pareto_scores: │

│ { │

│ 0: {"V1": 1.0, "V2": 0.0, "V3": 0.0, "V4": 1.0} │

│ } │

│ │

│ Average score: 0.5 (2 out of 4 correct) │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Key point: We used VALSET here, not trainset. This gives us a baseline score.

Iteration 1: The Main Loop Begins

Now the real optimization starts. This is where TRAINSET and VALSET play different roles.

Step 1.1: Sample Minibatch from TRAINSET

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Step 1.1: Sample minibatch from TRAINSET │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ BatchSampler (EpochShuffledBatchSampler) does: │

│ │

│ 1. Shuffle trainset indices: [T3, T7, T1, T9, T5, T2, T8, T4, T6]│

│ │

│ 2. Take first minibatch_size=3: [T3, T7, T1] │

│ │

│ minibatch = [ │

│ {"id": "T3", "question": "If x+3=7, what is x?", ...}, │

│ {"id": "T7", "question": "Solve: 2x=10", ...}, │

│ {"id": "T1", "question": "What is 2+2?", ...}, │

│ ] │

│ │

│ Note: This is from TRAINSET, not valset! │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Step 1.2: Evaluate Current Candidate on Minibatch (WITH TRACES)

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Step 1.2: Run candidate on minibatch, capture traces │

│ ───────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ adapter.evaluate(minibatch, candidate, capture_traces=TRUE) │

│ │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ T3: "If x+3=7, what is x?" │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ TRACE CAPTURED: │ │

│ │ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ System prompt: "Answer the math question." │ │ │

│ │ │ User input: "If x+3=7, what is x?" │ │ │

│ │ │ Model reasoning: "The answer is 7+3=10" │ │ │

│ │ │ Model output: "10" │ │ │

│ │ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Expected: "4" │ │

│ │ Score: 0.0 ✗ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ FEEDBACK: "Model didn't solve for x, just computed │ │

│ │ 7+3 instead of recognizing this as an │ │

│ │ equation to solve." │ │

│ ├──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ T7: "Solve: 2x=10" │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ TRACE CAPTURED: │ │

│ │ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ System prompt: "Answer the math question." │ │ │

│ │ │ User input: "Solve: 2x=10" │ │ │

│ │ │ Model reasoning: "2 times 10 is 20" │ │ │

│ │ │ Model output: "20" │ │ │

│ │ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Expected: "x=5" │ │

│ │ Score: 0.0 ✗ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ FEEDBACK: "Model multiplied instead of dividing. │ │

│ │ Didn't recognize 'Solve' means find x." │ │

│ ├──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ T1: "What is 2+2?" │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ TRACE CAPTURED: │ │

│ │ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ │ System prompt: "Answer the math question." │ │ │

│ │ │ User input: "What is 2+2?" │ │ │

│ │ │ Model reasoning: "2 plus 2 equals 4" │ │ │

│ │ │ Model output: "4" │ │ │

│ │ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Expected: "4" │ │

│ │ Score: 1.0 ✓ │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ Minibatch average: 0.33 (1 out of 3 correct) │

│ │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Critical difference from valset evaluation:

- Here we capture traces (the full reasoning process).

- These traces are used for reflection (understanding WHY it failed).

Step 1.3: Reflection — Analyze Failures

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Step 1.3: Reflect on failures using reflection_lm │

│ ────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ The ReflectiveMutationProposer sends this to GPT-4: │

│ │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ REFLECTION PROMPT: │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Current instruction: "Answer the math question." │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Here are some examples of how this instruction performed:│ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Example 1 (FAILED, score=0.0): │ │

│ │ Input: "If x+3=7, what is x?" │ │

│ │ Model reasoning: "The answer is 7+3=10" │ │

│ │ Model output: "10" │ │

│ │ Expected: "4" │ │

│ │ Feedback: Model didn't solve for x... │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Example 2 (FAILED, score=0.0): │ │

│ │ Input: "Solve: 2x=10" │ │

│ │ Model reasoning: "2 times 10 is 20" │ │

│ │ Model output: "20" │ │

│ │ Expected: "x=5" │ │

│ │ Feedback: Model multiplied instead of dividing... │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Example 3 (SUCCESS, score=1.0): │ │

│ │ Input: "What is 2+2?" │ │

│ │ Model output: "4" │ │

│ │ Expected: "4" │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Analyze what went wrong and propose an improved │ │

│ │ instruction that fixes these issues. │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ GPT-4 RESPONDS: │

│ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Analysis: │ │

│ │ The current instruction fails on algebra problems │ │

│ │ because it doesn't tell the model to: │ │

│ │ 1. Recognize equations vs arithmetic │ │

│ │ 2. Solve for variables when present │ │

│ │ 3. Show step-by-step work │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Improved instruction: │ │

│ │ "Read the math problem carefully. If it contains a │ │

│ │ variable (like x), solve for that variable step by │ │

│ │ step. Otherwise, compute the answer directly. Show │ │

│ │ your reasoning." │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Step 1.4: Create New Candidate (Mutation)

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Step 1.4: Create mutated candidate │

│ ────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ OLD candidate (index 0): │

│ { │

│ "instruction": "Answer the math question." │

│ } │

│ │

│ NEW candidate (index 1): │

│ { │

│ "instruction": "Read the math problem carefully. If it │

│ contains a variable (like x), solve for │

│ that variable step by step. Otherwise, │

│ compute the answer directly. Show your │

│ reasoning." │

│ } │

│ │

│ candidates list is now: │

│ [ │

│ candidate_0, ← original │

│ candidate_1 ← NEW (mutated) │

│ ] │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Step 1.5: Evaluate New Candidate on VALSET

Now we switch back to VALSET. This is the "exam" to see if our improvement actually worked.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Step 1.5: Evaluate NEW candidate on VALSET │

│ ────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ VALSET EVALUATION (capture_traces=FALSE, just need scores) │

│ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ V1: "What is 9+6?" │ │

│ │ New prompt: "Read the math problem carefully..." │ │

│ │ Model output: "9+6=15. The answer is 15." │ │

│ │ Score: 1.0 ✓ │ │

│ ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ V2: "Solve: 3x=12" │ │

│ │ New prompt: "Read the math problem carefully..." │ │

│ │ Model output: "This has variable x. 3x=12, so │ │

│ │ x=12÷3=4. The answer is x=4." │ │

│ │ Score: 1.0 ✓ ← Was 0.0 before! IMPROVEMENT! │ │

│ ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ V3: "Sara has 8 cookies, eats 3. How many left?" │ │

│ │ New prompt: "Read the math problem carefully..." │ │

│ │ Model output: "Sara starts with 8, eats 3. │ │

│ │ 8-3=5. She has 5 cookies left." │ │

│ │ Score: 1.0 ✓ ← Was 0.0 before! IMPROVEMENT! │ │

│ ├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ │ V4: "What is 6×7?" │ │

│ │ New prompt: "Read the math problem carefully..." │ │

│ │ Model output: "6×7=42. The answer is 42." │ │

│ │ Score: 1.0 ✓ │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ Updated pareto_scores: │

│ { │

│ 0: {"V1": 1.0, "V2": 0.0, "V3": 0.0, "V4": 1.0}, ← old │

│ 1: {"V1": 1.0, "V2": 1.0, "V3": 1.0, "V4": 1.0} ← NEW │

│ } │

│ │

│ Candidate 1 average: 1.0 (4 out of 4 correct!) │

│ Candidate 0 average: 0.5 (2 out of 4 correct) │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Step 1.6: Update Pareto Frontier and Best

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Step 1.6: Update tracking │

│ ───────────────────────── │

│ │

│ Pareto frontier analysis: │

│ │

│ Candidate 0: [1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0] on V1,V2,V3,V4 │

│ Candidate 1: [1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0] on V1,V2,V3,V4 │

│ │

│ Does candidate 1 DOMINATE candidate 0? │

│ • V1: 1.0 >= 1.0 ✓ │

│ • V2: 1.0 > 0.0 ✓ (strictly better!) │

│ • V3: 1.0 > 0.0 ✓ (strictly better!) │

│ • V4: 1.0 >= 1.0 ✓ │

│ │

│ YES! Candidate 1 dominates candidate 0. │

│ Candidate 0 is NO LONGER on the Pareto frontier. │

│ │

│ Pareto frontier = [candidate_1] │

│ Best candidate = candidate_1 │

│ Best score = 1.0 │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Step 1.7: Checkpoint and Continue

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Step 1.7: Save checkpoint, increment iteration │

│ ────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ Save to run_dir/checkpoint.pkl: │

│ { │

│ "candidates": [candidate_0, candidate_1], │

│ "pareto_scores": {0: {...}, 1: {...}}, │

│ "best_candidate_idx": 1, │

│ "best_score": 1.0, │

│ "iteration": 1, │

│ "metric_calls": 8 (4 initial + 4 this iteration) │

│ } │

│ │

│ iteration = 2 │

│ │

│ Check stop condition: │

│ • max_metric_calls = 500? We've used 8. Continue. │

│ • File "gepa.stop" exists? No. Continue. │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Iteration 2: Continue the Loop

Now let's see how it continues:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ ITERATION 2 │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ Step 2.1: Select candidate to evolve │

│ ────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ ParetoCandidateSelector looks at frontier: [candidate_1] │

│ Only one candidate on frontier, so select candidate_1 │

│ │

│ Step 2.2: Sample NEW minibatch from TRAINSET │

│ ───────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ Continue from shuffled order: [T3, T7, ... T8, T4, T6] │

│ │

│ Next 3: [T9, T5, T2] │

│ │

│ minibatch = [ │

│ {"id": "T9", "question": "Rectangle area?", ...}, │

│ {"id": "T5", "question": "John has 3 apples...", ...}, │

│ {"id": "T2", "question": "What is 5×3?", ...}, │

│ ] │

│ │

│ Step 2.3: Evaluate candidate_1 on minibatch (WITH TRACES) │

│ ─────────────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ T9: Score 1.0 ✓ │

│ T5: Score 1.0 ✓ │

│ T2: Score 1.0 ✓ │

│ │

│ Average: 1.0 (perfect!) │

│ │

│ Step 2.4: skip_perfect_score = True │

│ ────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ Since all scores are perfect (1.0), there's nothing to │

│ learn from these examples. Skip reflection! │

│ │

│ new_candidate = None (no mutation this iteration) │

│ │

│ Step 2.5: Continue to next iteration │

│ ──────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ iteration = 3 │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Key insight: When skip_perfect_score=True and the prompt scores perfectly on the minibatch, GEPA doesn't waste time reflecting. It moves to different training examples.

Iteration 3: Finding Harder Examples

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ ITERATION 3 │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ Step 3.1: Select candidate_1 (still only one on frontier) │

│ │

│ Step 3.2: Sample next minibatch: [T8, T4, T6] │

│ │

│ Step 3.3: Evaluate candidate_1 on minibatch │

│ │

│ T8: "What is 7+8?" → Score 1.0 ✓ │

│ T4: "What is 10÷2?" → Score 1.0 ✓ │

│ T6: "What is 8-3?" → Score 1.0 ✓ │

│ │

│ Still perfect! Skip reflection again. │

│ │

│ Step 3.4: End of epoch! │

│ ───────────────────── │

│ │

│ We've now seen all 9 training examples. │

│ │

│ BatchSampler reshuffles for next epoch! │

│ New order: [T5, T1, T8, T3, T9, T6, T4, T2, T7] │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

The Complete Data Flow Diagram

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ GEPA DATA FLOW │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ ┌───────────────────┐ ┌───────────────────┐ │

│ │ TRAINSET │ │ VALSET │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ T1, T2, T3... │ │ V1, V2, V3, V4 │ │

│ │ (many examples) │ │ (held-out test) │ │

│ └─────────┬─────────┘ └─────────┬─────────┘ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Sample minibatch │ Full evaluation │

│ │ (3 examples) │ (all examples) │

│ │ │ │

│ ▼ │ │

│ ┌───────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ EXECUTE WITH │ │ │

│ │ TRACE CAPTURE │ │ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ │ "Why did this │ │ │

│ │ fail?" │ │ │

│ └─────────┬─────────┘ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Traces + Scores │ │

│ │ │ │

│ ▼ │ │

│ ┌───────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ REFLECTION │ │ │

│ │ (GPT-4) │ │ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ │ "The prompt │ │ │

│ │ failed because │ │ │

│ │ ... Try this │ │ │

│ │ instead..." │ │ │

│ └─────────┬─────────┘ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ New candidate prompt │ │

│ │ │ │

│ ▼ │ │

│ ┌───────────────────┐ │ │

│ │ NEW CANDIDATE │──────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │ Evaluate on valset │

│ │ "Read the math │ (no traces needed, │

│ │ problem..." │ just scores) │

│ └─────────┬─────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ │ Scores on each validation example │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌───────────────────┐ │

│ │ PARETO FRONTIER │ │

│ │ UPDATE │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ "Is this prompt │ │

│ │ better? On │ │

│ │ which tasks?" │ │

│ └─────────┬─────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ │ Updated frontier │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌───────────────────┐ │

│ │ NEXT ITERATION │──────────────────┐ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ │ Select candidate │ │ │

│ │ from frontier │ │ │

│ └───────────────────┘ │ │

│ ▲ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ └────────────────────────────┘ │

│ LOOP │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Summary: The Two Data Paths

| Aspect | TRAINSET Path | VALSET Path |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Learn from mistakes | Measure true performance |

| When used | During reflection | After creating new candidate |

| How much | Small minibatch (3-5 examples) | All examples (or sample) |

| Traces captured? | YES (need to analyze) | NO (just need scores) |

| Output | Insights → New prompt | Scores → Pareto frontier |

| Analogy | Practice problems | Final exam |

Why This Separation Matters

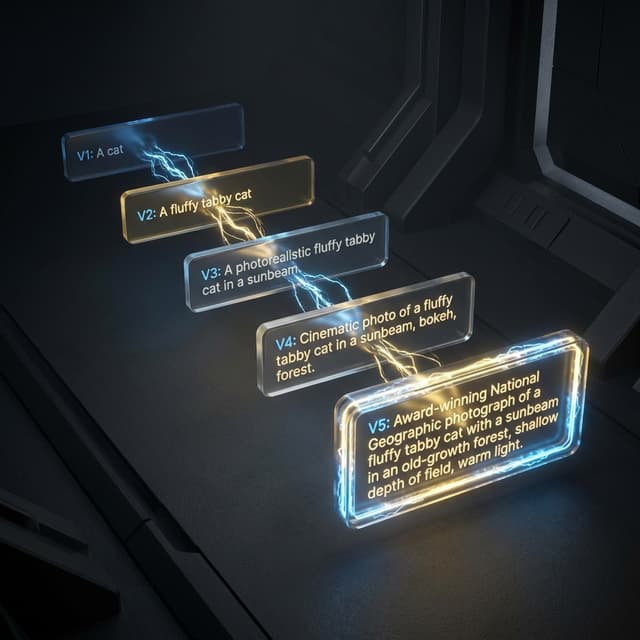

Problem: Overfitting to Training Data

If we only used trainset for both learning AND scoring:

- Iteration 1: Learn from T1, T2, T3 → Create prompt that's perfect for T1, T2, T3

- Iteration 2: Score on T1, T2, T3 → "100%! We're done!"

- But on new data (V1, V2, V3, V4): "40%... oops"

The prompt memorized the practice test instead of learning to solve math.

Solution: Separate Validation

- Iteration 1: Learn from T1, T2, T3 → Create prompt | Score on V1, V2, V3, V4 → "60%... needs improvement"

- Iteration 2: Learn from T4, T5, T6 → Refine prompt | Score on V1, V2, V3, V4 → "80%... getting better"

- Iteration 3: Learn from T7, T8, T9 → Refine prompt | Score on V1, V2, V3, V4 → "95%... almost there"

By scoring on held-out data, we ensure the prompt generalizes to new problems it hasn't seen during training.

Code Location Summary

Here's where each step happens in the code:

# In ReflectiveMutationProposer.propose():

# Step 1: Sample from TRAINSET

minibatch = self.batch_sampler.sample(self.trainset) # ← TRAINSET

# Step 2: Evaluate WITH traces

eval_result = self.adapter.evaluate(

minibatch,

candidate,

capture_traces=True # ← Capture traces for reflection

)

# Step 3: Reflect and create new candidate

new_text = self._reflect_and_propose(...)

return new_candidate

# In GEPAEngine.run():

# Step 4: Evaluate new candidate on VALSET

state = self._evaluate_candidate(state, new_idx)

# In GEPAEngine._evaluate_candidate():

# Get validation examples

val_ids = self.val_evaluation_policy.select_validation_ids(

self.valset, # ← VALSET

state.iteration

)

val_batch = [self.valset[i] for i in val_ids]

# Evaluate WITHOUT traces (just need scores)

outputs, scores = self.evaluator(val_batch, candidate)

# Update Pareto scores

for val_id, score in zip(val_ids, scores):

state.pareto_scores[candidate_idx][val_id] = score

Understanding Candidate Selection and Evaluation Counts

Setup: Realistic Dataset Sizes

# TRAINSET: 100 examples (used for learning/reflection)

trainset = [

{"id": f"T{i}", "question": f"...", "answer": f"..."}

for i in range(100)

]

# VALSET: 50 examples (used for scoring/Pareto frontier)

valset = [

{"id": f"V{i}", "question": f"...", "answer": f"..."}

for i in range(50)

]

# TESTSET: 50 examples (NEVER touched during optimization - final evaluation only)

testset = [

{"id": f"X{i}", "question": f"...", "answer": f"..."}

for i in range(50)

]

# Configuration

reflection_minibatch_size = 5 # Learn from 5 examples at a time

max_metric_calls = 1000 # Budget: 1000 total evaluations

Part 1: How Many Validation Evaluations?

The Formula

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ VALIDATION EVALUATION COUNTING │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ With FullEvaluationPolicy: │

│ │

│ val_evals_per_candidate = len(valset) = 50 │

│ │

│ Total val evals = 50 × (number of candidates evaluated) │

│ │

│ ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ With max_metric_calls = 1000: │

│ │

│ Max candidates we can evaluate = 1000 ÷ 50 = 20 candidates │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Step-by-Step Counting

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ METRIC CALLS BREAKDOWN │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ ITERATION 0 (Initialization) │

│ ──────────────────────────── │

│ • Evaluate seed_candidate on valset │

│ • 50 validation examples × 1 candidate = 50 metric calls │

│ │

│ Running total: 50 │

│ │

│ ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ ITERATION 1 │

│ ─────────── │

│ • Trainset minibatch: 5 examples (for reflection, but these │

│ DON'T count toward metric_calls in most implementations) │

│ • New candidate created │

│ • Evaluate new candidate on valset: 50 metric calls │

│ │

│ Running total: 100 │

│ │

│ ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ ITERATION 2 │

│ ─────────── │

│ • Trainset minibatch: 5 examples │

│ • New candidate created │

│ • Evaluate on valset: 50 metric calls │

│ │

│ Running total: 150 │

│ │

│ ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ ... continuing pattern ... │

│ │

│ ITERATION 19 │

│ ──────────── │

│ • New candidate created │

│ • Evaluate on valset: 50 metric calls │

│ │

│ Running total: 1000 ← HIT BUDGET, STOP! │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Summary Table

| Budget (max_metric_calls) | Valset Size | Max Candidates | Max Iterations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 50 | 10 | ~9 |

| 1000 | 50 | 20 | ~19 |

| 2000 | 50 | 40 | ~39 |

| 1000 | 100 | 10 | ~9 |

| 1000 | 25 | 40 | ~39 |

Key insight: Smaller valset = more iterations within same budget, but less reliable scores.

Part 2: When and How is the Next Candidate Selected?

The Selection Happens BEFORE Trainset, AFTER Valset

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ ITERATION TIMELINE │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ END OF ITERATION N-1 │

│ ──────────────────── │

│ │ │

│ │ Valset evaluation completed │

│ │ Pareto frontier updated │

│ │ pareto_scores = { │

│ │ 0: {V1: 0.8, V2: 0.6, V3: 0.9, ...}, │

│ │ 1: {V1: 0.9, V2: 0.7, V3: 0.8, ...}, │

│ │ 2: {V1: 0.7, V2: 0.9, V3: 0.7, ...}, │

│ │ } │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ START OF ITERATION N │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ╔═════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╗ │

│ ║ STEP 1: SELECT CANDIDATE ║ │

│ ║ ──────────────────────── ║ │

│ ║ ║ │

│ ║ CandidateSelector.select(candidates, pareto_scores) ║ │

│ ║ ║ │

│ ║ Uses VALSET scores to decide which candidate to evolve ║ │

│ ║ ║ │

│ ║ Output: candidate_idx = 2 (for example) ║ │

│ ╚═════════════════════════════════════════════════════════╝ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ STEP 2: SAMPLE TRAINSET MINIBATCH │ │

│ │ ───────────────────────────────── │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ minibatch = [T23, T47, T89, T12, T56] (5 examples) │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ STEP 3: EVALUATE SELECTED CANDIDATE ON MINIBATCH │ │

│ │ ───────────────────────────────────────────────── │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Run candidate_2 on [T23, T47, T89, T12, T56] │ │

│ │ Capture traces for reflection │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ STEP 4: REFLECT AND MUTATE │ │

│ │ ────────────────────────── │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Analyze failures → Create candidate_3 (new!) │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ STEP 5: EVALUATE NEW CANDIDATE ON VALSET │ │

│ │ ──────────────────────────────────────── │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Run candidate_3 on ALL 50 valset examples │ │

│ │ Update pareto_scores[3] = {V1: ..., V2: ..., ...} │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ STEP 6: UPDATE PARETO FRONTIER │ │

│ │ ─────────────────────────── │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Recalculate which candidates are non-dominated │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ▼ │

│ END OF ITERATION N → START OF ITERATION N+1 │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Part 3: How Does Pareto Selection Actually Work?

The Pareto Scores Table

After 5 iterations, we have 6 candidates (seed + 5 mutations):

| Candidate | V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | V5 | V6 | V7 | V8 | ... |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.5 | ... |

| 1 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 | ... |

| 2 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | ... |

| 3 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 | ... |

| 4 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.8 | ... |

| 5 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.6 | ... |

BEST on each example:

- V1: Candidates 1, 3 tie at 0.9 (Both on frontier)

- V2: Candidate 2 wins at 0.9 (On frontier)

- V3: Candidate 4 wins at 0.9 (On frontier)

- V4: Candidate 3 wins at 0.9 (On frontier)

- V5: Candidate 2 wins at 0.8 (On frontier)

- V6: Candidate 4 wins at 0.9 (On frontier)

- V7: Candidate 5 wins at 0.9 (On frontier)

- V8: Candidate 4 wins at 0.8 (On frontier)

Computing the Pareto Frontier

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ DETERMINING THE PARETO FRONTIER │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ A candidate is on the Pareto frontier if it's BEST on at │

│ least ONE validation example. │

│ │

│ Candidate 0: Best on... nothing. DOMINATED (not on frontier) │

│ Candidate 1: Best on V1 (tied). ON FRONTIER │

│ Candidate 2: Best on V2, V5. ON FRONTIER │

│ Candidate 3: Best on V1, V4, and many others. ON FRONTIER │

│ Candidate 4: Best on V3, V6, V8. ON FRONTIER │

│ Candidate 5: Best on V7. ON FRONTIER │

│ │

│ Pareto frontier = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5} │

│ Dominated = {0} │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Computing Coverage (Selection Probability)

"Coverage" = Number of validation examples where this candidate achieves the BEST score.

Think of it like sports rankings. If candidate 3 holds the record on 25 out of 50 tracks, it gets 50% of the coaching attention. Candidate 5, which only holds the record on 4 tracks, gets 8%.

Assuming 50 validation examples total:

| Candidate | Coverage | Probability |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0% (Dominated) |

| 1 | 3 | 3/50 = 6% |

| 2 | 8 | 8/50 = 16% |

| 3 | 25 | 25/50 = 50% (Most likely!) |

| 4 | 10 | 10/50 = 20% |

| 5 | 4 | 4/50 = 8% |

| TOTAL | 50 | 100% |

Selection is WEIGHTED RANDOM based on coverage:

┌────┬────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ │▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓▓ │

│ 0% │ 6% │ 16% │ 50% │ 20% │ 8% │

│ │ C1 │ C2 │ C3 │ C4 │C5 │

└────┴────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Roll random number 0-100:

- 0-6: Select candidate 1

- 6-22: Select candidate 2

- 22-72: Select candidate 3

- 72-92: Select candidate 4

- 92-100: Select candidate 5

Part 4: Can Good Candidates Be Left Out?

The "Left Out" Problem

Imagine you have a "specialist" candidate. It's amazing at one specific type of problem but mediocre everywhere else.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ THE "LEFT OUT" PROBLEM │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ Scenario: Candidate 5 is a "specialist" │

│ ───────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ Candidate 5 is AMAZING at one specific type of problem │

│ (let's say V7, V12, V38, V45 - all word problems) │

│ │

│ But it's mediocre on everything else. │

│ │

│ Coverage: Only 4 out of 50 = 8% selection probability │

│ │

│ ──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────│

│ │

│ With 19 iterations total: │

│ │

│ Expected selections of candidate 5 = 19 × 0.08 = 1.5 │

│ │

│ That means: │

│ • Candidate 5 might only be selected 0, 1, or 2 times │

│ • Its "specialty" might not get evolved further │

│ • We might miss discovering an even better word-problem prompt│

│ │

│ ──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────│

│ │

│ Meanwhile, candidate 3 (the "generalist"): │

│ │

│ Expected selections = 19 × 0.50 = 9.5 times │

│ │

│ Candidate 3 gets MUCH more evolution attention! │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

| Iteration | Random Roll | Selected | New Candidate Created |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45% | 3 | Candidate 6 (from 3) |

| 2 | 18% | 2 | Candidate 7 (from 2) |

| 3 | 55% | 3 | Candidate 8 (from 3) |

| 4 | 31% | 3 | Candidate 9 (from 3) |

| 5 | 89% | 4 | Candidate 10 (from 4) |

| 6 | 62% | 3 | Candidate 11 (from 3) |

| 7 | 94% | 5 | Candidate 12 (from 5) ←! |

| 8 | 27% | 3 | Candidate 13 (from 3) |

| 9 | 71% | 3 | Candidate 14 (from 3) |

| 10 | 15% | 2 | Candidate 15 (from 2) |

| 11 | 48% | 3 | Candidate 16 (from 3) |

| 12 | 83% | 4 | Candidate 17 (from 4) |

| 13 | 39% | 3 | Candidate 18 (from 3) |

| 14 | 3% | 1 | Candidate 19 (from 1) |

| 15 | 66% | 3 | Candidate 20 (from 3) |

| 16 | 52% | 3 | Candidate 21 (from 3) |

| 17 | 78% | 4 | Candidate 22 (from 4) |

| 18 | 41% | 3 | Candidate 23 (from 3) |

| 19 | 97% | 5 | Candidate 24 (from 5) ←! |

SELECTION COUNTS:

- Candidate 1: 1 time

- Candidate 2: 2 times

- Candidate 3: 11 times (DOMINATED the evolution!)

- Candidate 4: 3 times

- Candidate 5: 2 times (Only 2 chances to evolve)

Candidate 5's "word problem specialty" got limited attention.

Part 5: Is This a Problem? And What Are the Solutions?

Why GEPA Does This (The Argument FOR)

Think of it like funding startups. If company A is succeeding in 50% of markets and company B is only succeeding in 8%, where would you put your money?

GEPA's logic: If candidate 3 is best on 50% of problems, evolving it is more likely to yield a good general solution. Candidate 5's niche might just stay niche.

Solutions to the Specialist Problem

Solution 1: Epsilon-Greedy Selection

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ EPSILON-GREEDY SELECTION │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ With epsilon = 0.1: │

│ • 90% of the time: Select the BEST candidate (by avg score) │

│ • 10% of the time: Select RANDOMLY from all candidates │

│ │

│ This guarantees every candidate has at least 10% ÷ N chance │

│ of being selected (where N = number of candidates) │

│ │

│ ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ Example with 6 candidates: │

│ • 90% → Select candidate 3 (best average) │

│ • 10% → Random among all 6 │

│ │

│ Candidate 5's selection probability: │

│ • From Pareto: 0% │

│ • From random: 10% × (1/6) = 1.67% │

│ • Total: 1.67% │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Solution 2: More Iterations (Bigger Budget)

More lottery tickets = more chances for specialists to win.

- With 19 iterations: Expected selections of candidate 5 = 1.5

- With 100 iterations: Expected selections of candidate 5 = 8

- With 500 iterations: Expected selections of candidate 5 = 40

Solution 3: Smaller Validation Set (Use Sampling)

Instead of evaluating on ALL 50 valset examples, evaluate on a RANDOM SAMPLE of 10 each time.

- PROS: 5× more iterations, more exploration, specialists get more chances.

- CONS: Pareto scores are NOISY, might keep "lucky" candidates or discard "unlucky" ones.

Solution 4: Merge Proposer (Combine Specialists)

Even if a specialist isn't selected for mutation often, it can still contribute via MERGING. Think of it like cross-breeding: take the word-problem skills from candidate 5 and combine them with the algebra skills from candidate 3.

This way, niche insights get incorporated into generalist prompts.

Part 6: Complete Flow Summary

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ COMPLETE GEPA FLOW WITH NUMBERS │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ SETUP: │

│ • Trainset: 100 examples │

│ • Valset: 50 examples │

│ • Minibatch size: 5 │

│ • Budget: 1000 metric calls │

│ │

│ ═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════ │

│ │

│ ITERATION 0: Initialize │

│ ──────────────────────── │

│ • Evaluate seed on valset: 50 metric calls │

│ • Total metric calls: 50 │

│ • Candidates: [C0] │

│ • Pareto frontier: [C0] │

│ │

│ ═══════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════ │

│ │

│ ITERATION 1-19: Main loop (repeated until budget exhausted) │

│ ─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── │

│ │

│ For each iteration: │

│ │

│ 1. SELECT: Pick candidate from Pareto frontier │

│ └─ Based on valset scores (coverage-weighted) │

│ │

│ 2. SAMPLE: Get 5 examples from trainset │

│ └─ Epoch-shuffled, ensures all 100 seen over ~20 iterations │

│ │

│ 3. EXECUTE: Run selected candidate on minibatch │

│ └─ Capture traces for reflection │

│ │

│ 4. REFLECT: Analyze failures with GPT-4 │

│ └─ Generate improved prompt │

│ │

│ 5. CREATE: Add new candidate to pool │

│ └─ Candidates grow: [C0] → [C0,C1] → [C0,C1,C2] → ... │

│ │

│ 6. EVALUATE: Score new candidate on valset │

│ └─ 50 metric calls per new candidate │

│ │

│ 7. UPDATE: Recalculate Pareto frontier │

│ └─ Some candidates may become dominated │

│ │

│ 8. CHECK: Budget exhausted? │

│ └─ If metric_calls >= 1000, stop │

│ │

│═════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════│

│ │

│ FINAL STATE: │

│ ───────────── │

│ • ~20 candidates created │

│ • ~1000 metric calls used │

│ • Pareto frontier: Maybe 5-10 candidates │

│ • Best candidate: Highest average score on valset │

│ │

│═════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════│

│ │

│ AFTER OPTIMIZATION (not part of GEPA): │

│ ───────────────────────────────────── │

│ • Evaluate best candidate on TESTSET │

│ • This gives true generalization performance │

│ • Testset was NEVER seen during optimization │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Key Takeaways

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| How many valset evaluations? | len(valset) × num_candidates (with FullEvaluationPolicy) |

| When is selection done? | At START of each iteration, BEFORE trainset sampling |

| What determines selection? | Pareto frontier from VALSET scores (coverage-weighted) |

| How many times is a candidate selected? | Proportional to its coverage (could be 0 to many times) |

| Can good candidates be left out? | YES — specialists with low coverage may rarely be selected |

| What are the mitigations? | Epsilon-greedy, more budget, sampling, or merge proposer |